About The McCluskey Model

THE McCLUSKEY MODEL FOR EXPLORING THE DYNAMICS OF ATTACHMENT IN ADULT LIFE

Introduction

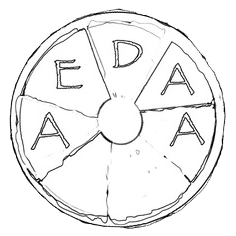

The McCluskey Model uniquely brings three strands together – a theory of interaction (Goal Corrected Empathic Attunement), a model of working so that exploration can be clear and uncluttered (Exploratory Goal Corrected Psychotherapy), and a focus for the exploration which is the organisation of the systems identified by Heard and Lake. In essence, the Model offers an opportunity for us to identify, explore and in many cases resolve unprocessed experiences linked to the seven instinctive biological systems of Careseeking, Caregiving, Self-defence, Interest-sharing, Sexuality, their personally created External Environment and their Internal Environment.

These seven systems working together, form what Heard and Lake referred to as the Restorative Process. This process is activated when an individual perceives a threat to their survival or well-being. Its primary function is to restore equilibrium and promote well-being. The Restorative Process provides a clear framework for understanding emotional arousal and self-regulation—one that supports human development, vitality, and overall mental health.

At its core, the McCluskey Model encourages us to reduce fear and relate to others in non-competitive, authentic ways. By stepping out of dominant–submissive relational dynamics, we can begin to appreciate our own strengths and experiences while engaging with others from a place of mutual respect.

When I learn to recognize the systems active within me—when I can identify my emotional states, understand their causes, and notice how I experience arousal—I can make more intentional choices. I can access these systems as a restorative process, supporting my journey toward optimal well-being.

If we have not been met as a person—truly seen, heard, and supported—it becomes difficult to meet others in the same way. Instead, we may fall into patterns of control, withdrawal, or compliance. The task, then, is to ease fear, foster genuine connection, and embrace relationship as a source of healing.

A short introduction to the seven systems

Careseeking. We are born care seeking and with the instinctive need to be cared for by another. Repeated experiences from infancy onwards of having our needs understood, attended to and met by another person, a caregiver, enables us to build trust in ourselves and in others. We learn that caregivers can be a source of support and emotional regulation. We also learn the value of turning to another person in times of need and, if we receive effective care and help from them, we feel relief and more able to continue with our everyday life.

We know that not everyone has consistent experiences of having their careseeking needs met. This can be for many reasons. Within the McCluskey Model we recognise that when our careseeking has not been met, we carry the pain of this within. It may lead to us becoming less able to care seek and trust another. We can gradually learn it is safer to manage alone rather than to face the distress of rejection, inconsistency or sustained misattunement from others. This helps us survive but often at the expense of our full wellbeing. We know when this has happened it can be a vulnerable and difficult step to re-start careseeking and looking to another person for help. However, we also believe with support and understanding our skills and confidence as a careseeker can increase and with this can come improvements in our overall wellbeing and ability to live with more curiosity and freedom.

Caregiving. As human beings we also have an instinctive capacity to give care especially to those that we have an emotional connection or attachment with. Our capacity for caregiving is often aroused when we see someone in need or distress. This can be described as a ‘goal corrected system’ because when we are able to offer care and have this received by another person, the goal of our care giving is met. Just as the care seeker feels relief through receiving effective care, so does the caregiver when they have been able to meet or help meet another’s need.

In order to be effective, caregiving needs to remain exploratory, companionable and non-defensive. When we are able to be exploratory as a caregiver, we are much more likely to be able to be able to empathically attune to the other person, understand their need and offer effective help. In contrast, when the needs of the careseeker or the way they go about seeking care unsettles, confuses or frighten us, we may start to act from the fear system and risk either minimizing, dismissing or intruding unhelpfully or in a dominating fashion. The setting in which we give care can also have a significant impact, if as a caregiver we feel supported and settled in ourselves we are much more likely to be fully available to respond to a careseeker.

Self-defence and Fear

Our system for self-defence is split into two within the McCluskey Model, firstly we have our instinctive, primitive fear system survival response and secondly our newer (in evolutionary terms) careseeking response.

The instinctive fear system is an intrapersonal system, it does not depend on another person and activates extremely fast, out of conscious awareness, whenever we perceive a threat. In contrast, at the heart of the careseeking response, is an interpersonal and relational connection. If we can access the help of another, when experiencing a threat of some sort, it allows us to survive with wellbeing.

When we experience a threat, and our fear system is aroused all areas of our lives can be impacted. Crucially we lose the ability to be exploratory. One of the key aspects of the McClusky Model is to learn to recognise the arousal of the fear system and the impact it has. Through this we can become more skilled at moving from coping alone to seeking the support and understanding of another. Depending on the level of threat, the activation of the fear system may be subtle or much more extreme as in the case of a threat to life.

The way we defend ourselves is highly influenced by the processes we have built up through our relationships with others, for example where we’ve had support and been reminded of our competence. This enables us to navigate challenges. However, we know that past experience often interferes with how we manage in the present. If we have repeatedly not been met as a person and consequently struggle to meet others as people, we are likely to move into behaving in dominant or submissive ways. When we have experienced other people as a source of threat, this can have a big impact on how we go about seeking help. The Model helps us explore how to ease off the fear and learn to behave more relationally – delighting in our own skills and experience and sharing competence and creativity with others.

The model also raises the idea of healthy self-defence and the important capacity of learning to look out for ourselves.

Interest Sharing

Our interest sharing system as adults emerges from our early instinctive experiences of curiosity, exploration and play. Whilst our interests can often be explored on our own, it seems when we join up with another(s) who has a similar level of interest to us, it can be an important source of connection. This sharing draws people closer together and leads to increased feelings of vitality and wellbeing. Interest sharing holds the potential to generate energy and creativity. The mutuality that arises between people linked to interest sharing is described as a peer relationship. In this system we meet and are met through our interests.

The interest sharing system can be neglected when we are facing difficulties in life. It is also impacted when our systems for caregiving or careseeking are aroused and we are managing our own or another’s distress or need. As with other systems, our interest sharing is linked to our early experiences including the interests of those we grew up around and the levels of support we had to notice and access our interests. Our interests also develop as we get older and we can move beyond what was of interest in our family or school, to discover new areas of interest throughout life and through these new connections with others.

The system for sex and sexuality

The sexual system emerges from the fact that we are born explorers in the world and sex is part of this exploration. For some it also plays a procreative role. In a positive way it is an expression of our self and a source of intimacy and vitality. As a system it is closely connected to careseeking, caregiving and interest sharing.

It can also be connected to unsupportive experiences and the activation of the fear system. With the latter, our focus may become more on self-defence and self-regulation through sex rather than the intimacy of interpersonal connection. Notions of love and attractiveness sometimes cause us to become confused or ashamed of our feelings and connections with others. This can lead to fear, shame and isolation.

Perhaps of all the systems, sexuality is affected the most by the external influences of the cultures and practices of our immediate family and peers and by our local society and culture. It is also informed by the media, by the creation of idolatry and artificial sexual standards for instance idealised/unreal images of the human body. It is based in (or limited by) the language we are allowed to use within the confines of religious, cultural and familial and social structures as well as influenced by social media and popular culture.

Internal Environment

Our internal environment is made up of our experiences in relationships from birth. It is likely that it is also influenced by earlier intergenerational experiences. It can be described as our internal hard drive. It is constantly evolving and changing based on our interactions and what we are taking in from the world around us. This system is based on Bowlby’s notion of the Internal Working Model (IWM). We can think of our internal environment as a combination of our experiences from the past, the present and the way we learn to anticipate or imagine a future.

Through our relational and social experiences, we come to hold memories, beliefs and physical bodily experience within. Significant moments, either very good or very bad may have especially great influence on how our internal environment works. These can all combine to give us a predominantly supportive inside sense of ourselves or an unsupportive, harsh or critical one. We can often experience both and may notice that certain situations arouse a greater or lesser sense of internal support.

This system is an intrapersonal system that is both influenced by all the other systems for example through the care we have received or the people we have been able to interest share with. In turn it influences all the other systems. We may for example feel we are not worthy of care or need to manage alone.

External environment

Our external environment is the space or place we develop for ourselves in the world. Sometimes it is referred to the personally created external environment. Although we are always located within a wider social, political and cultural context, it has a particularly direct relationship to our early experiences of the place where we grew up. This early experience of home may have supported us, it may also have been challenging and hold painful memories. We tend to be drawn to places that connect us back to earlier experiences of wellbeing, comfort and safety.

Often this area of experience is under explored yet it has huge significance because it relates to so many areas of our lives. These include both where and how we feel most settled, our relationship to routines and rituals, to the work we do, to how we dress and decorate ourselves and how homes, our relationship with food, with money, with cultural objects, with colour and temperature, with external space and the natural world and much more. Of course, it also relates to what we need or long for and to lack of resources, opportunity, circumstances or support. So, it is an area of our lives that can be connected to deep sadness and absence as well as enriching and supportive times. We seem to know environments that support us deep inside and when we are in them, we can feel both ease and energy. When we share space or live with other people, we have to find ways to navigate the many different experiences and needs for what home is. This can create conflict or remain unresolved and create ongoing stress within ourselves and our relationships.

We understand this area of our lives to be an important resource and source of support when we are not able to access another person for care if we are in need. Our external environment can help to calm and regulate us or it can magnify our struggles and become another aspect of our life that undermines our wellbeing. We rely on our external environment to support, validate and enrich our sense of self.